A Remembrance by Joel E. Gingold

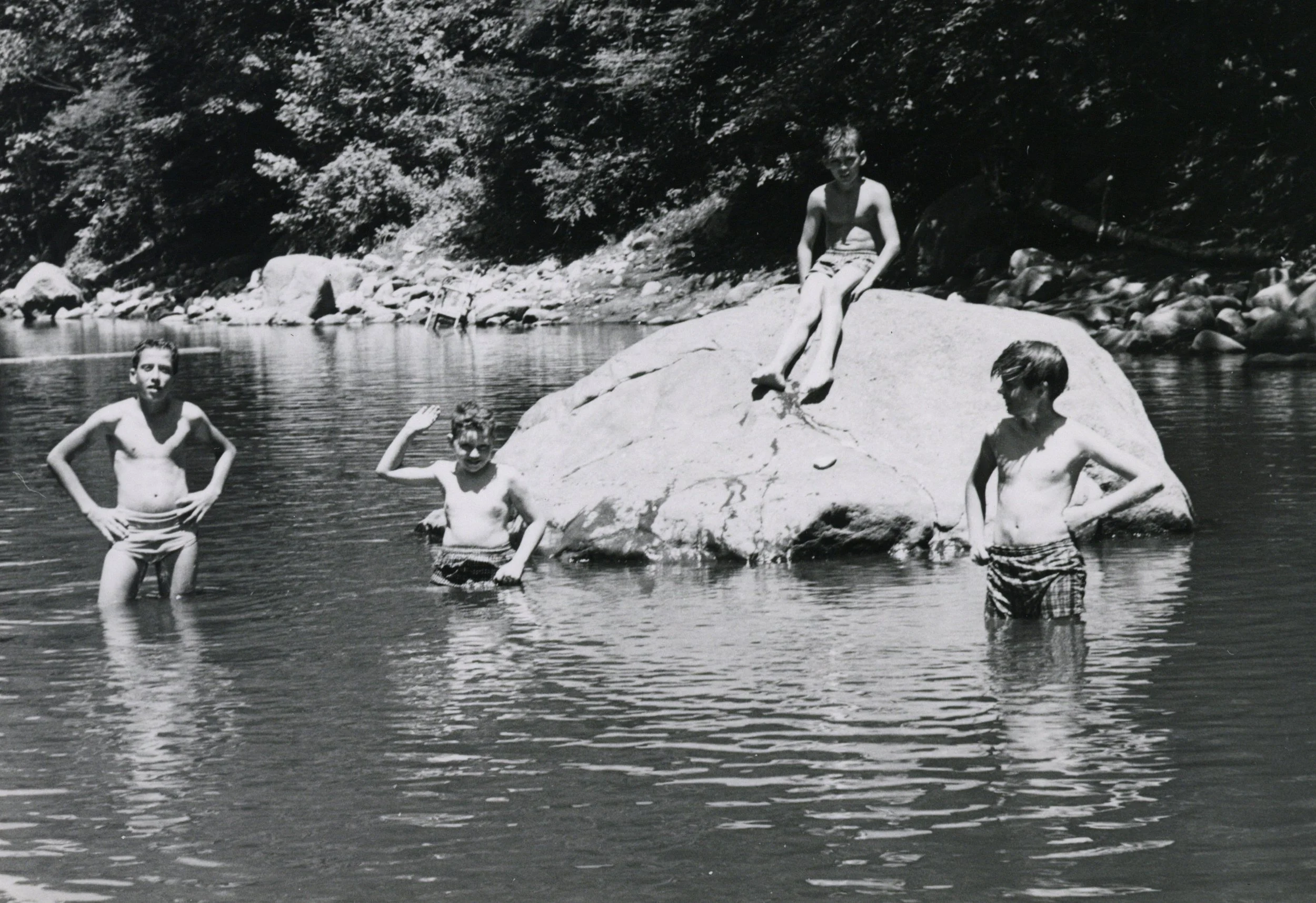

Circa 1950s photo of the upper section of Silver Lake.

It is neither silver nor is it a lake, but Silver Lake has been an integral and iconic part of Croton for nearly a century. For all of that time, individuals and families have descended the hill to bask on the beach, refresh themselves in the cool (often, too cool!) waters of the Croton River, and meet with friends, all in an exquisite sylvan setting. I have been a devotee since the 1940s.

While the village as a whole has expanded markedly in the years since World War II, the same is not true of Silver Lake. Certainly, all of its facilities have been substantially upgraded, but the range of its aquatic activities has sadly declined.

Back in the day, as some might say, neither the breakwater nor the dam had yet been installed. The beach swept down the hill unimpeded to the water’s edge, and standing at the shoreline, one faced directly upstream. The area adjacent to the beach, then called the Shallow End, was inhabited principally by small children, non-swimmers, and adults who just wanted to cool off with a quick dip.

Three naturally occurring rocks, unimaginatively dubbed First Rock, Second Rock, and Third Rock, were at increasing distances from the shore, at increasing depths, and of increasing size. They were the yardsticks of kids’ swimming ability. As your prowess increased, you ventured to First, then to Second, and finally to Third Rock, which, when there was sufficient water in the river, was at a depth of five or six feet, or as we said then, “over your head.” Being able (and allowed) to swim to Third Rock, which is still there today, was a rite of passage for kids in Croton.

Typical Silver Lake crowd in the 1940s, with the raft and Third Rock on the left.

But the major departure from the current arrangement was the Deep End. Upstream, along the rocks, a diving board had been installed (the foundation is still there), as had a slide into the river. Anchored out in the stream were two large wooden rafts, one of which contained a diving board as well as a diving tower. Regrettably, when the rafts deteriorated over the years, they were not replaced.

Third Rock when water was low.

As soon as you became a capable swimmer, you navigated the rocky foot trail from the beach, or swam upstream, and spent the bulk of your time enjoying the well-earned marvels of the Deep End, along with teenagers and those adults who could tolerate the village’s youth. While not officially a part of Silver Lake’s equipment, a rope had been fastened to one of the trees on the Cortlandt side of the river, and aspiring Tarzans launched themselves into space, splashing down in the stream.

Eat your heart out, Tarzan!

But all was not perfect. The few amenities that did exist were pretty primitive. There were no modern sanitary facilities, only a couple of pit toilets that practically no one used except when in extremis, and there was no running water. The changing rooms, if you could call them that, were simple, unroofed wooden stockades, one side for men, the other for women. The staff was continually patching holes bored through the dividing wall between the two sections. Most people changed into and out of their bathing suits at home.

The ubiquitous horseflies were even more numerous and more savage than today. One season, one of the lifeguards offered a dollar (big bucks in those days) to anyone who brought him a jar containing a hundred or more dispatched horseflies.

It was not uncommon for Croton kids to pack a lunch, hop on their bicycles, and spend the entire day at Silver Lake, unaccompanied by their parents. There were far fewer alternative summer activities for kids back then, and they were granted a lot more freedom.

Every year, the Recreation Department conducted a swim meet at Silver Lake, and races were held for every age group. Medals were presented to all of the winners and a large crowd was usually in attendance to cheer them on.

Of course, everyone knew that if you got back into the water in less than an hour after eating, you would suffer severe stomach cramps and surely drown. So, after lunch we would “hop rocks” downstream of the swimming area for the requisite sixty minutes. And to the delight of the kids, and the chagrin of their parents, the Good Humor man made a daily appearance.

The rules governing the use of Silver Lake were much less draconian than they are today. You could access the beach and the river at any time, with the understanding that if lifeguards weren’t on duty, you swam at your own risk. Even many years later, during my commuting days, on a hot summer evening after I returned from the city, we packed up the kids and some sandwiches, went down to Silver Lake, cooled off in the river, and enjoyed a very pleasant picnic on the beach.

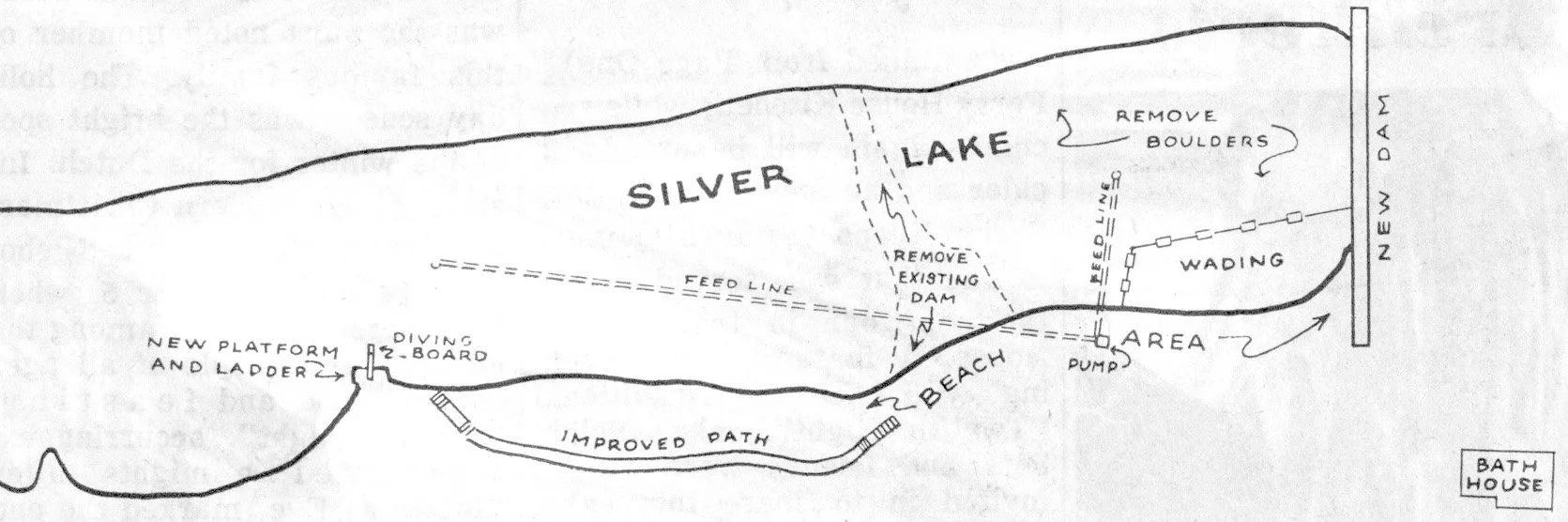

In 1960 a group called Citizens for Silver Lake proposed improvements to accommodate everyone from toddlers to experienced swimmers.

There was no limit on the number of people who could enjoy the beach at any time. Contemporary news articles reported crowds of several hundred at Silver Lake on hot summer weekends and for special events like the swimming races. It’s really a disgrace that, due to all of the regulations imposed by Westchester County, this gem of a facility is only available to us for a couple of months during the year and even then, access is restricted on heavy demand days.

During the fall of 1955, a major hurricane roared through our area. There was significant flooding throughout the village, and for a time, the village water pumps were out of commission. Undaunted, we all brought containers to the Municipal Building where a fleet of tanker trucks brought fresh water to Croton each day.

What we did not realize at the time was that there were concerns about possible damage to the New Croton Dam. Why New York City waited ten months to inspect the dam is still a mystery.

For the summer of 1956, I had secured one of the coveted lifeguard positions at Silver Lake. Notwithstanding the hordes of staff that swarm over the beach today, we worked the much larger swimming area with only four lifeguards. We were all there on weekends and holidays, but during the week, there were typically just three guards patrolling the whole area. We were on duty essentially the entire day, with only a couple of short breaks for lunch, etc. There was a surfboard and even a boat to facilitate the rare rescue.

There was another thing that was unique about my experience at Silver Lake in 1956. The other three lifeguards were all young women. Joan Burguiere served as director and the other lifeguards were Ellen Mitchell and Alberta Whitfield. Today, women comprise a large fraction of the Silver Lake staff, but back in the 1950s that was practically unheard-of. While you might think that this was an ideal arrangement for a seventeen-year-old boy, it had its downside. Guess who had to do all of the heavy lifting?

We even caught the attention of the New York Daily News. They sent a reporter and a photographer to Croton to do a story on the “all-girl lifeguard force.” They were really disappointed to find that I was there as well, and I didn’t even get a mention until the very last paragraph of the article.

Future Olympian at the old diving board.

The first several weeks of the summer were rather routine, and we were occupied with our normal duties of opening, closing, and maintaining the beach, the occasional rescue of a small child, conducting swimming classes for nervous children, and trying to maintain order among our unruly classmates who frequented the beach. But that all changed one Friday afternoon in August.

It was late in the day with only a modest number of people on the beach and fewer in the water. All of a sudden, something very strange began to occur. It wasn’t immediately clear exactly what was happening, but the water level seemed to be rising, slowly at first, but then with a lot more force.

This post-flood photo was published in the August 9, 1956 issue of the Croton-Cortlandt News with the caption “Salvaging equipment at Silver Lake as the frigid rushing waters rise. ‘Doc’ Acocella, Joel Gingold and Ronnie Santana (in rear) drag the children’s slide to a safe place on the beach.”

Within minutes, torrents of water were sweeping down the river carrying away all of the equipment that was not secured as well as a large portion of the sand beach. Having had no warning, none of us had a plausible explanation. Had the dam burst?

With shrieking whistles, we immediately cleared all of the swimmers from the water and hustled everyone up to the higher levels of the beach. A call to the village office did nothing to solve the mystery, but it brought the recreation director, Doc Acocella, to the scene. We all stood watching dumbfounded as the raging river swallowed up almost the entire park. The diving board at the Deep End was elevated at about a sixty-degree angle.

By then, the water level had stabilized and the immediate threat had passed. News reports from the period estimated the water’s rise at five feet within five minutes. It was only the quick action of the Silver Lake staff (and plain good luck) that prevented any injuries—or worse. Had there been a large crowd in attendance, a tragedy could have ensued. Doc closed the beach for the foreseeable future, which turned out to be the balance of the swimming season.

It was only later we learned that New York City, in its infinite wisdom, had decided to open the blow-off gates at the base of the Croton Dam, lowering the water level in the reservoir to facilitate inspection of the dam to determine whether any damage had been done by the previous year’s hurricane. No notification had been given to Croton officials because, according to John H. Kelly, Eastern District Engineer for the NYC Department of Water Supply, “Our man wasn’t aware that a beach had been developed by Croton. He thought everyone had been notified.”

A swim meet sponsored by the Lions Club in August, 1943. Note the raft in the upper left.

That excuse rang hollow in light of the fact that Silver Lake had been a public beach for decades before the incident. To compound the offense, a city water supply department representative had visited Silver Lake the previous February to meet with village and county officials. They discussed improvements that would be made to the park later that spring, many of which were washed away by the city’s incompetence. It is ironic that advance notice was given to Black Rock, a private swimming club upstream of Silver Lake, which suffered only minimal damage in the flood.

The following morning, the Silver Lake staff, reinforced by other village employees, gathered on what was left of the beach to survey the damage and rescue the equipment that hadn’t already been washed away. With the attitudes that prevailed at the time, only the men were asked to enter the frigid, rushing waters (we were all pretty macho and thought we were being chivalrous). You think the river is cold this year? The water temperature on that day was recorded at 40-45 degrees Farenheit.

Working in three or four feet of rapidly flowing arctic water, we first had to detach the diving board and float it down to the beach where it could be extracted. Manipulating a wrench with numbed fingers to remove the nuts that secured it to the foundation was a Herculean task. Then we had to drag a freestanding slide installed in the Shallow End—which was no longer all that shallow—out of the water, and rescue a new lifeguard chair which, the previous day, sat on the beach well above the waterline, as well as securing whatever other equipment still remained within reach.

Due to the icy temperatures, we were only permitted to work in the water for brief periods, between which we took breaks to warm up and consume vast quantities of the steaming coffee that someone had thoughtfully brought down for the crew. So, a task that would have taken a relatively short time under normal conditions stretched out over several hours.

The lower section of Silver Lake in 1962, showing the sandy beach that is still used today.

Swimming never resumed that summer. The upper beach remained open as a play area for young children, supervised by Joan Burguiere. Ellen and Alberta were reassigned to other playgrounds around the village, and I spent the remainder of the summer working on maintenance projects for the Recreation Dept. Not exactly what I had signed up for.

The great flood is now just a memory for a few of our older residents, and the younger families that have moved into the village in the ensuing years are probably unaware, not only of this barely averted tragedy, but of the much wider variety of activities that were available at Silver Lake in years past, and the far greater freedom enjoyed by young people in that bygone era.

I still go down to Silver Lake several times each summer. The young children are still there, digging away, building sandcastles and throwing rocks into the water, just as I, and my children, and generations of others have done over the years. But the diving board and the slide are gone. And the rafts were never replaced. And I bet few people know why it’s called Third Rock. And very few swim in what was once the Deep End.

Silver Lake now has modern sanitation and changing facilities. But much has been lost over the decades. Perhaps, like many of my contemporaries, I’m just an old curmudgeon complaining that things were much better back then. But I still prefer the Silver Lake of my youth and crave the simpler and, in many ways, more fulfilling lives we led back then.

This article was first published in the Summer 2019 issue of The Croton Historian.