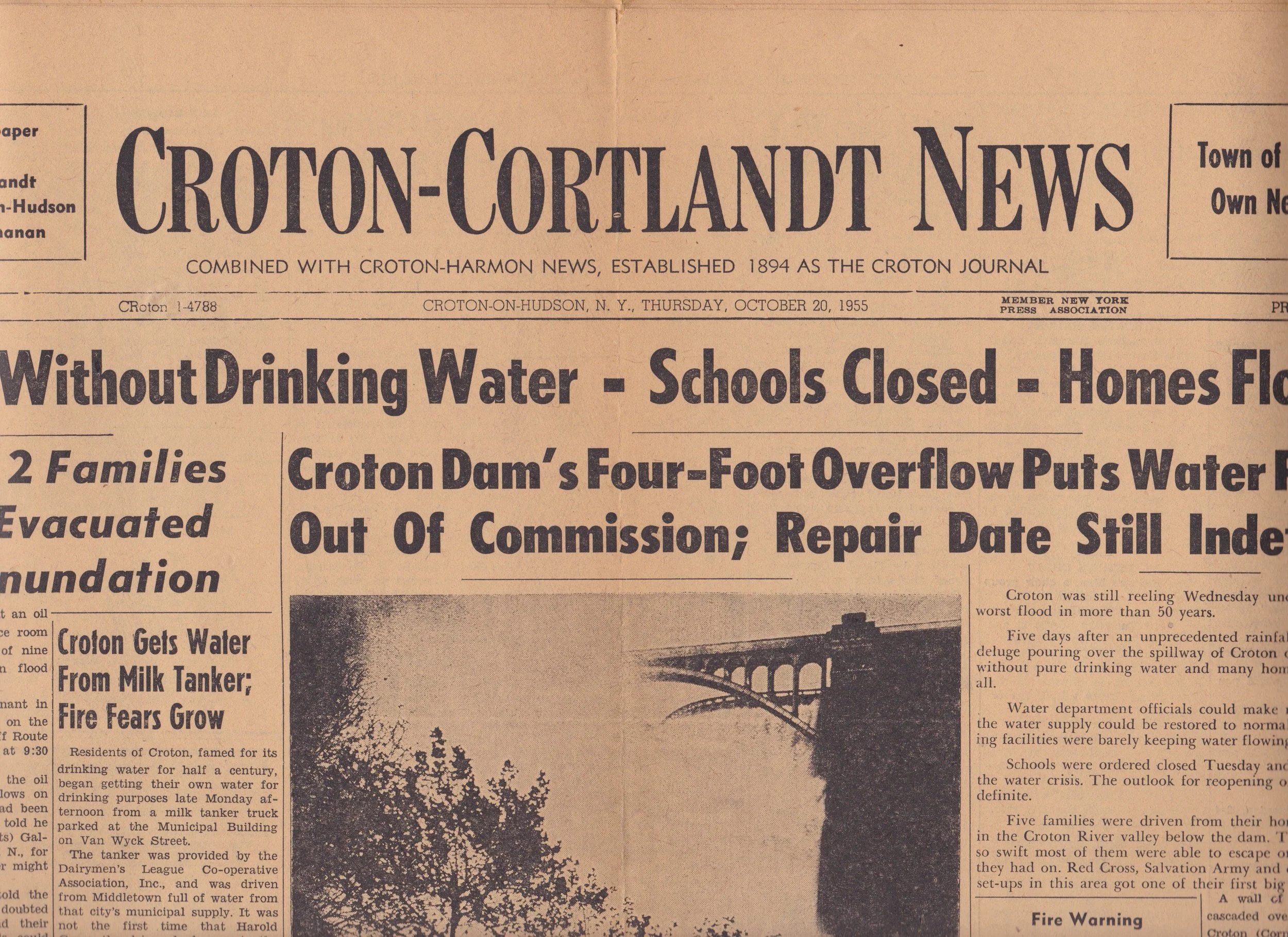

Detail of a larger photo of the ceremony that took place when the last stone was laid on the New Croton Dam on January 17, 1906. Croton Historical Society collection.

by Marc Cheshire, Village Historian

On January 17, 1906, the last stone was laid to complete the New Croton Dam.

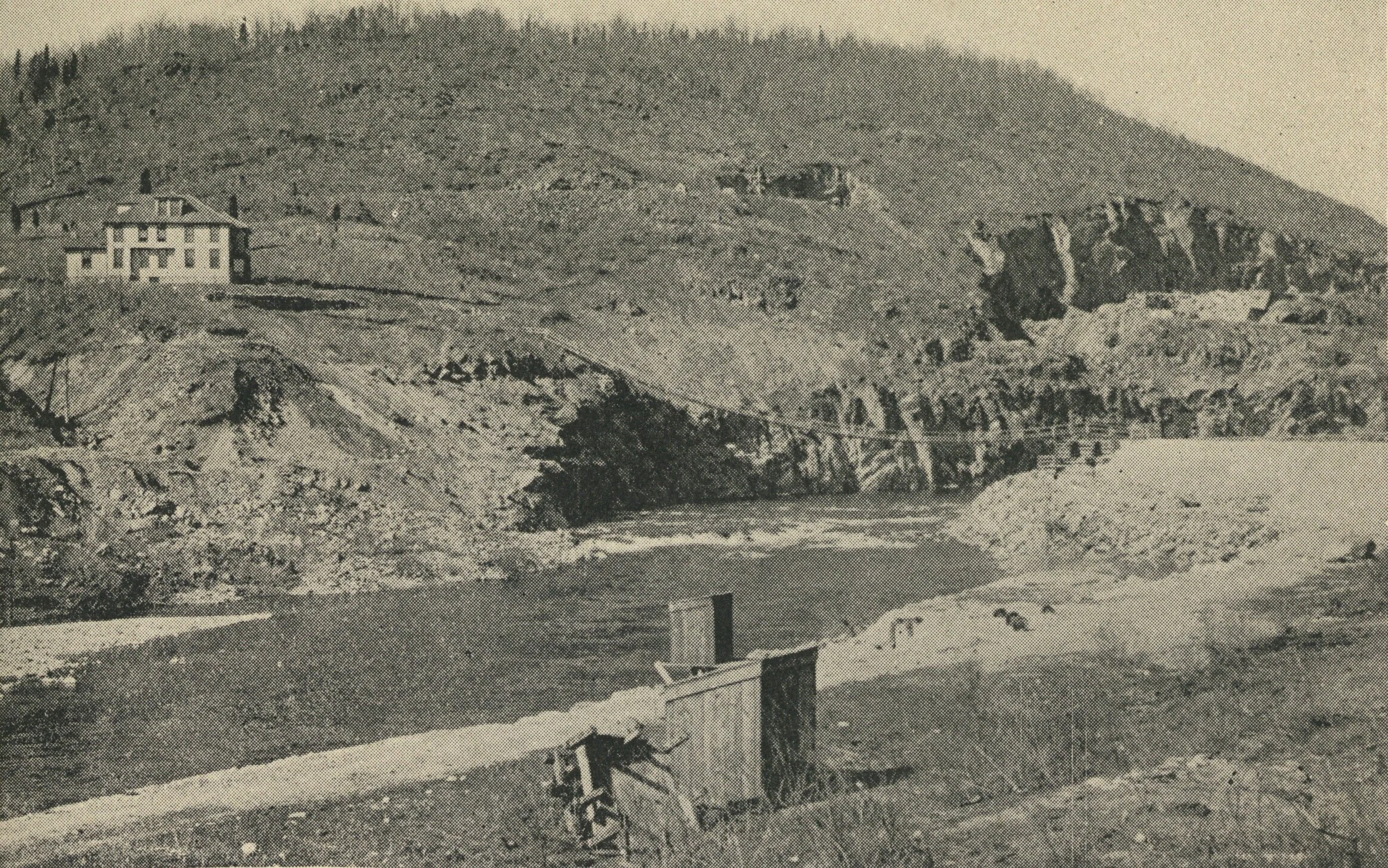

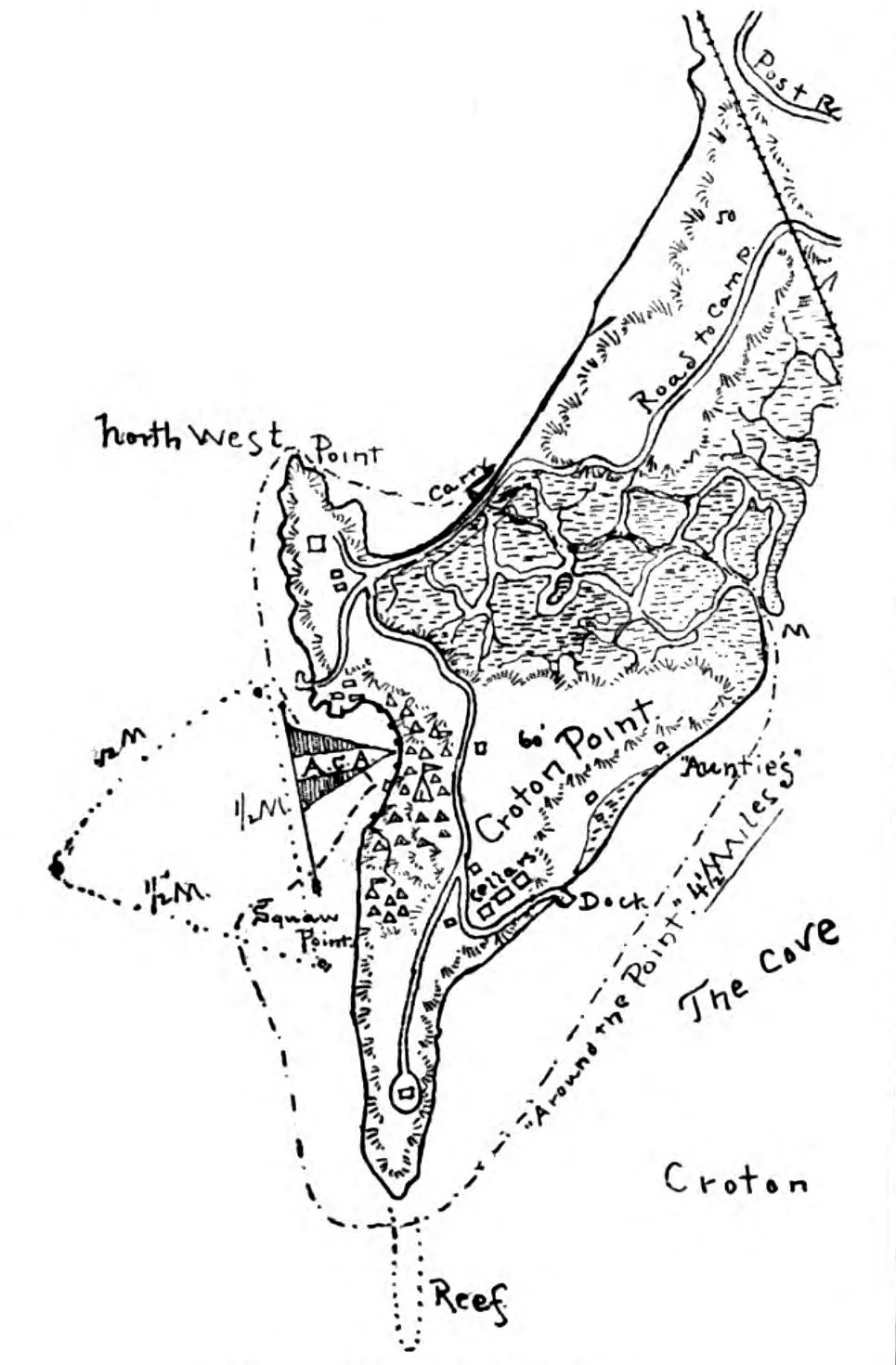

The dam took more than 14 years to build. Construction began on September 20, 1892, with excavation to divert the Croton River. A channel 125 feet wide and about a quarter of a mile long was blasted out of solid rock on the north side of the valley. A masonry wall 25 feet high was built along this channel, with earthen dams extending the wall at each end. After the river was diverted, more than 1.8 million cubic yards of earth and 400,250 cubic yards of rock were excavated to reach bedrock for the foundation.

Diverting the river and digging the massive hole for the foundation took four years—before a single stone for the foundation was laid. The project also included 15 bridges and 20 miles of new highways.

The maximum workforce was about 1,500 men. The average was 850 (475 on the dam, 375 at the quarry). Hundreds of pieces of heavy machinery were required, including 3 cableways, 75 derricks, 11 locomotives, 282 narrow-gauge cars, 3 steam shovels, 3 stone-crushing plants, and 8 concrete mixers.

All the stone was cut and shaped by hand. The dam is said to be the second or third largest hand-hewn stone structure in the world.

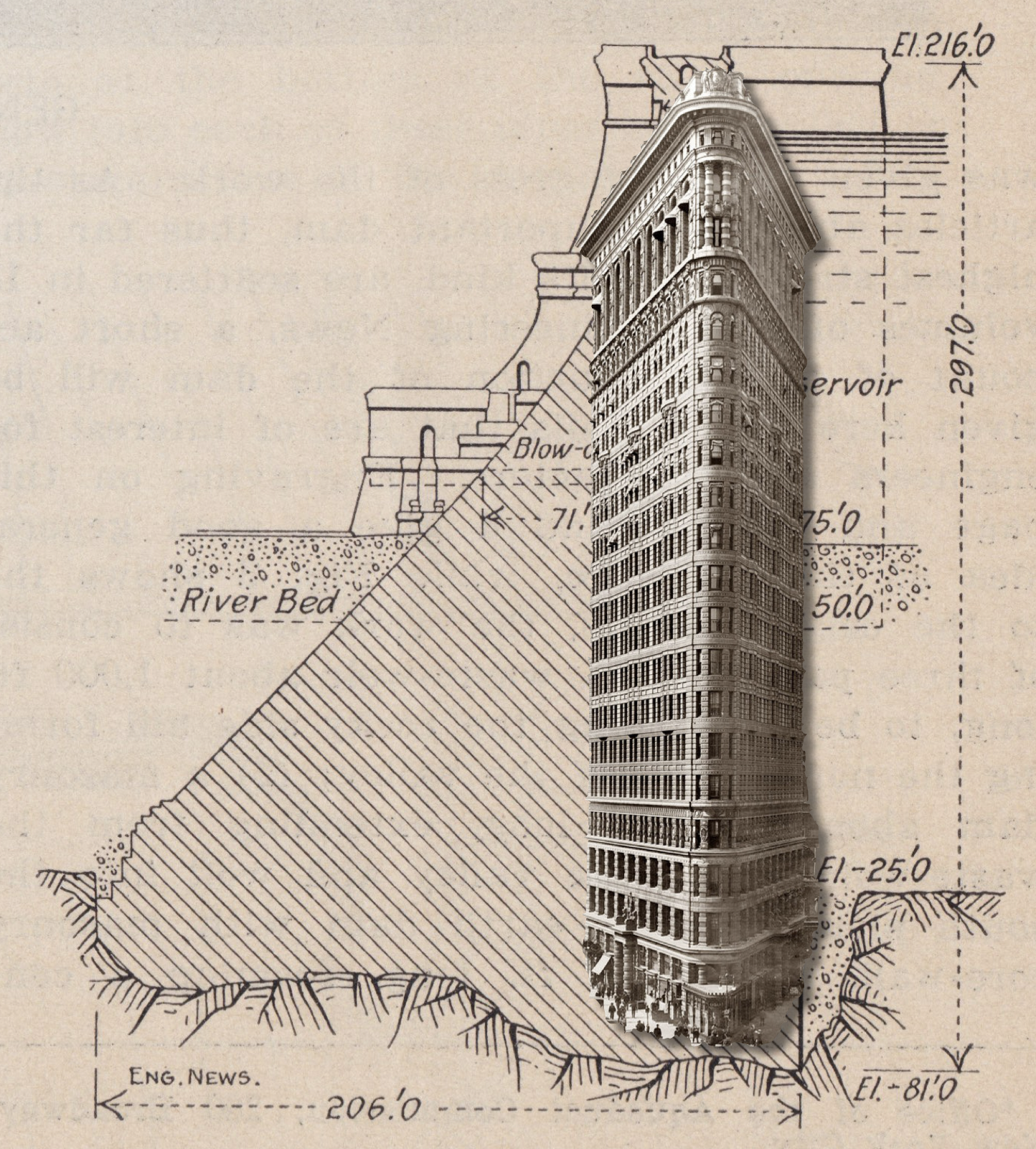

When you stand at the base of the dam and look up, you’re seeing only the top third of the structure. The rest is deep underground and the base is much wider than what is visible at the surface. New York City’s famous Flatiron Building would fit in the foundation and rise to the top of the dam.

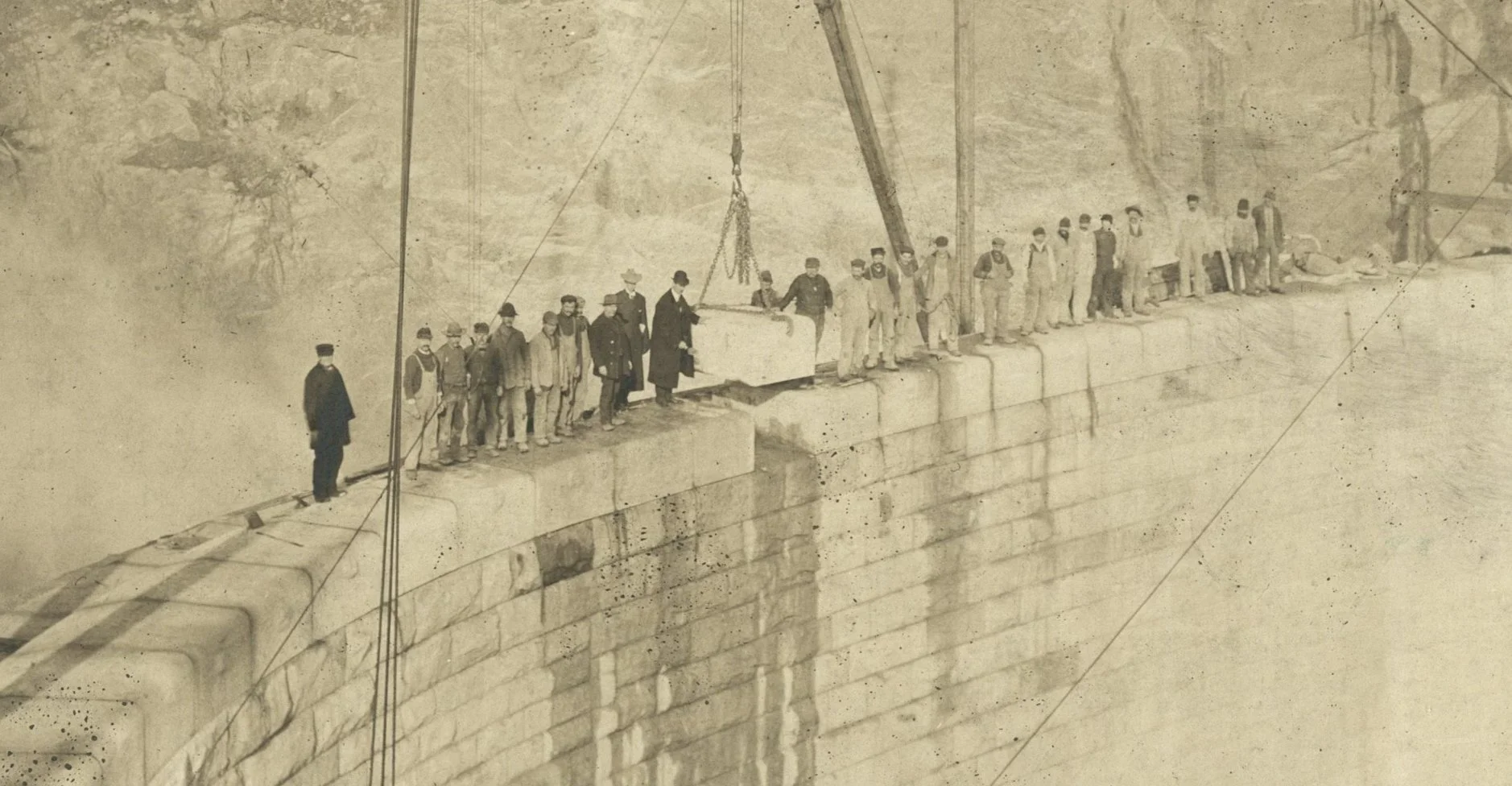

A rare photograph of the spillway area in the early days of the construction project, published in the June, 1897 issue of Metropolitan magazine. The building used by the contractors was removed after completion of the dam. Croton Historical Society collection.

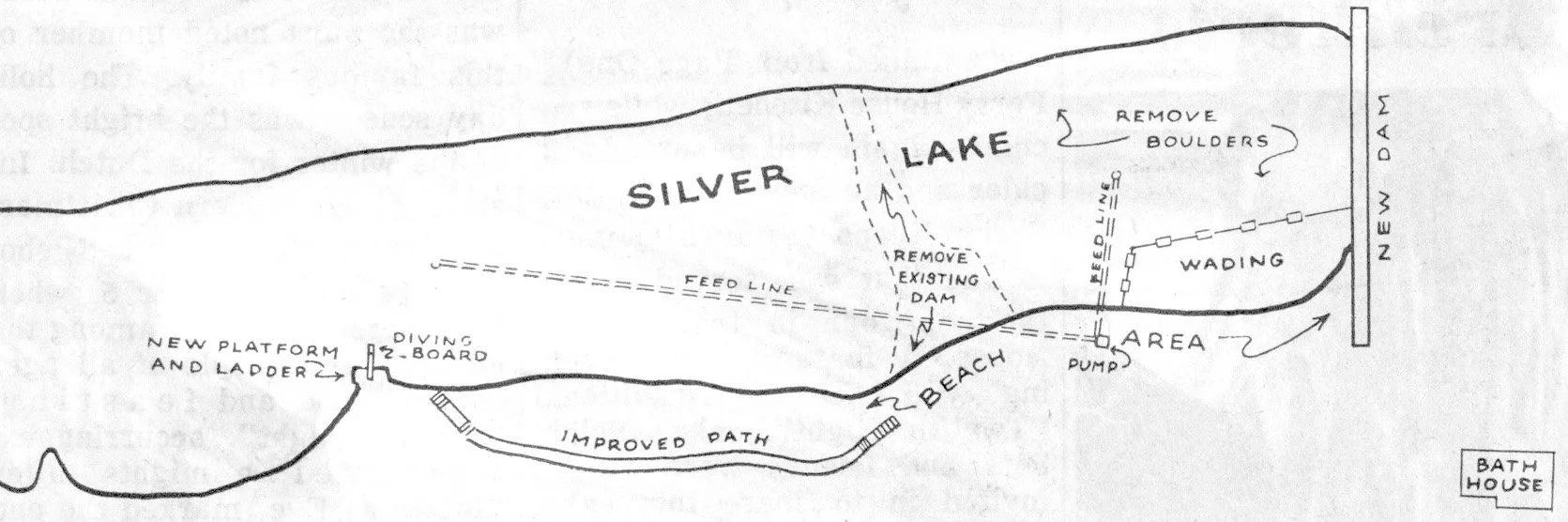

Diagram showing the diversion channel and original course of the Croton River, published in Scientific American in 1894. Croton Historical Society collection.

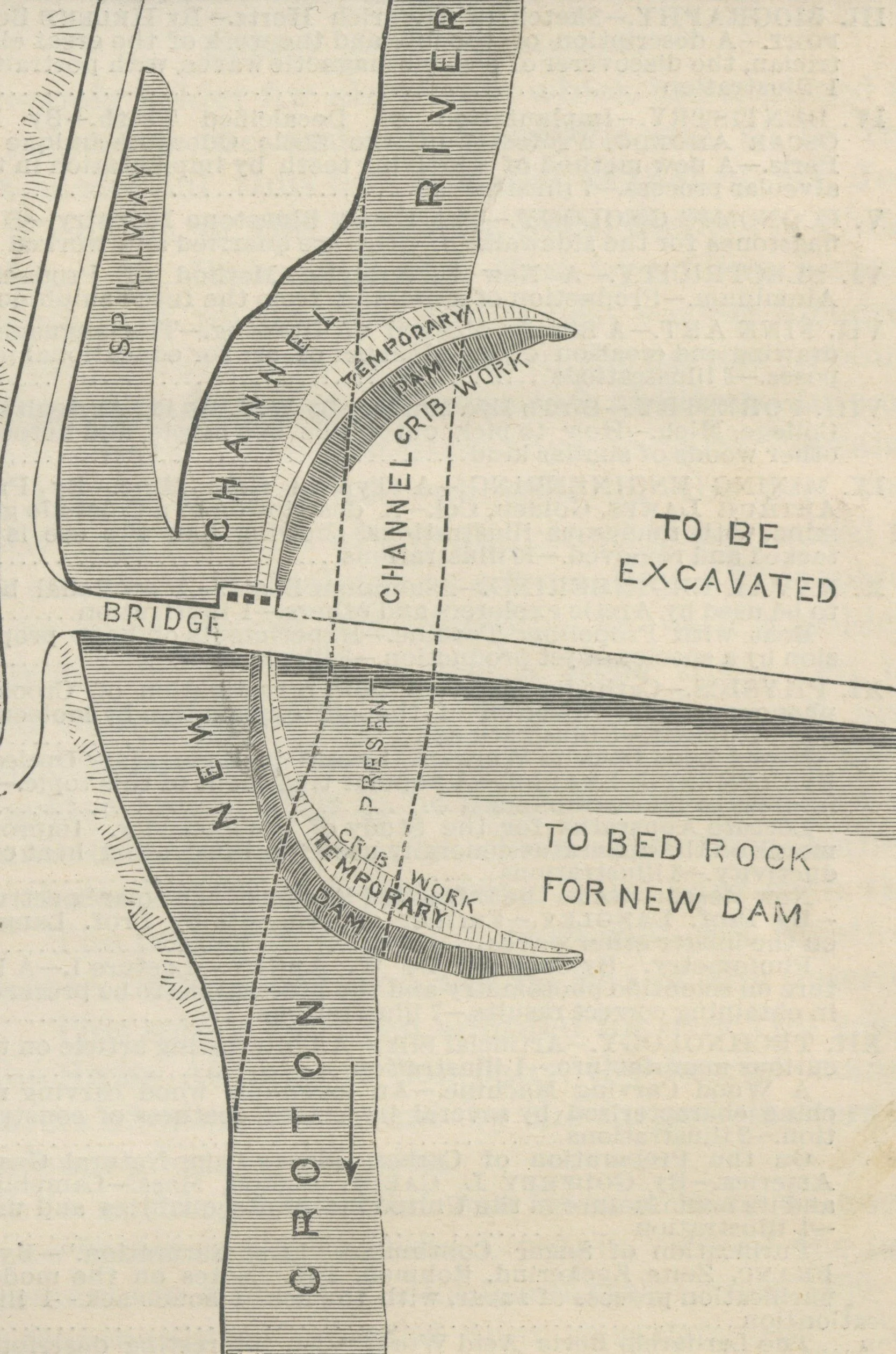

The massive hole dug for the foundation with the diversion channel in the foreground. The photograph was taken February 2, 1896. Croton Historical Society collection.

Most of the foundation of the New Croton Dam is deep underground. To get a sense of the scale, New York City’s famous Flatiron Building would fit in the foundation and rise to the top of the dam. Diagram from Engineering News, October 4, 1906. Photo collage by Marc Cheshire.

The switchback trail that leads up from the park below the dam to the Old Croton Aqueduct trail was originally a road for cars, shown in the foreground of this photograph. Croton Historical Society collection.

Peter P. Pullis took this photograph of the completed New Croton Dam for contractors Coleman, Breuchaud & Coleman on May 11, 1906. Croton Historical Society collection.